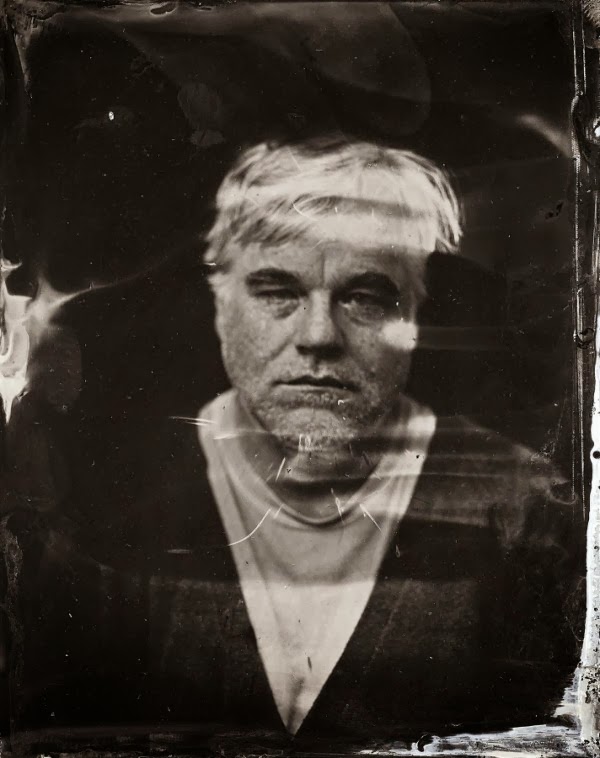

Sunday Afternoon, I'd arrived early to meet a friend in The Village, and as I stood waiting on the cold and windy street corner, I mindlessly scrolled through friends' updates on my phone. Several updates were expressing shock or sadness at the loss of some celebrity. Finally, someone used his initials, and after doing a Google search, I learned that only blocks from where I was standing, Philip Seymour Hoffman had overdosed and died. Right there, I burst into tears.

Hoffman was

undeniably a great actor – an unlikely movie star with a doughy body and a big

strawberry face that could be either warm and comforting, or menacing and cruel

in equal measure – an awkward sidekick with enough internal emotional intensity

to make him a compelling front man. Praised and loved by audiences, critics, and

colleagues alike, now he’s gone. Of course, I liked his work, (how could one

not admire his brave and improbable performances?), but it wasn’t the loss of a

great talent that struck me so sharply when I learned of his passing. It was

that, once again, one of my own had succumbed. With such a body of

work, so much success – family, career, money, fame, and prestige – why would

someone as fortunate and gifted as this guy use drugs? Addicts use. Simple.

This coming Sunday

I will have been without a drink or a drug for eleven years. My sobriety hasn’t

come easy and it’s certainly not something that I take lightly. Getting sober

is a treacherous and oftentimes soul-crushing challenge. Staying sober is

painstaking and tricky. One unfortunate truth is that life happens, and sometimes

it just plain sucks. Wouldn’t it be nice to “take the edge off” with a

glass of cabernet or a cocktail? How bad could that be, really? How dangerous is recreational marijuana use if it’s being legalized across the country? Not very is my guess. And

for a normal person those choices make perfect sense. But for someone like me, or someone like

Hoffman, once ignited, that ravenous and urgent inner need for relief and

comfort becomes paramount to all else, and can never be satisfied by simply

“taking the edge off.” I’m usually thinking about the third one before I’m

finished with the first. Whether or not one concedes with the theory that the alcoholic suffers from an allergy, this is my experience. Personal history has shown me that having momentary relief

leads me to seek oblivion – something “normal” people just don’t get, and this

unexplainable internal demand remains what makes addicts and alcoholics

different from other people.

I don’t think it

was part of his press packet, but I don’t think it was a well kept secret

either that Hoffman had been in recovery for more than two decades. So when

I learned of his death, I wept. I wept for him, for others I've known who've been lost to the disease, for those yet to be taken, for those yet to be saved, and for myself. I wept and I heard the message loud and clear:

long-term abstinence is not equivalent to a cure. I have a daily reprieve, that’s

all.

I’m grateful and

proud of my eleven years. They were painful, joyous, and hard-fought – I've earned

my place at the recovery table and I don’t ever want to lose it. So today I

will do what I did when I was new, and tomorrow I will do what I did when I was

new, and I’ll help others when I can, and if I’m lucky, I’ll continue to walk

in Grace. I am not a movie star, or a family man. I don’t have money, prestige,

fame, or a list of glistening credits to my name, but I understand who that man

was, and I understand him because I AM him. And by some Grace that I will never

understand, I have another chance to live in remission.

Just for today.